It was a rude awakening for the Cherokee in May 1838. Most people didn’t believe that the U.S. Government would actually remove the Cherokee people by force. But in late May 1838, five days before the deadline for voluntary removal, the U.S. Government began the process of forcibly removing the Cherokee people from their ancestral lands. Many people were forced to leave their homes quickly, given very little time to collect personal items, before being forced, sometimes at gunpoint, to interment in a stockade. Some Cherokees found themselves separated from their families. Their empty homes were left for white looters to ransack as they were led away. It is almost impossible to imagine what this experience must have been like. It is also difficult to understand what political and social issue led up to this event.

It was a rude awakening for the Cherokee in May 1838. Most people didn’t believe that the U.S. Government would actually remove the Cherokee people by force. But in late May 1838, five days before the deadline for voluntary removal, the U.S. Government began the process of forcibly removing the Cherokee people from their ancestral lands. Many people were forced to leave their homes quickly, given very little time to collect personal items, before being forced, sometimes at gunpoint, to interment in a stockade. Some Cherokees found themselves separated from their families. Their empty homes were left for white looters to ransack as they were led away. It is almost impossible to imagine what this experience must have been like. It is also difficult to understand what political and social issue led up to this event.

The removal of the Cherokee from their ancestral lands was long in the making. White encroachment was an old problem for the Cherokee. Throughout the history of the United States the sovereign right of the Cherokee over their lands was supported and protected, for the most part, by the U.S. Government until Andrew Jackson became President. In 1828, with Jackson’s support, Georgia claimed sovereignty over the Cherokee Nation. Not long after this in 1830 Congress, again with the support of Jackson, passed the Indian Removal Act. Gold had been discovered on Cherokee land and white settlers wanted the Cherokee gone.

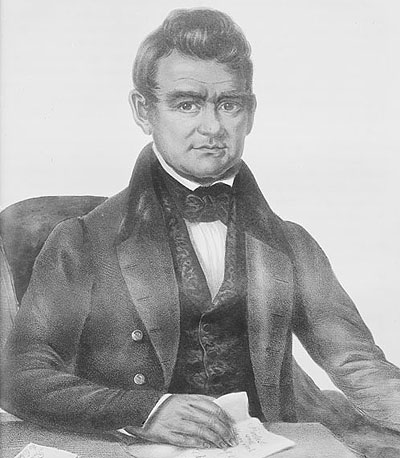

The Cherokee Nation fought both actions in the Supreme Court and their sovereignty was supported with a win (Worcester vs. Georgia in 1832). However the victory was hollow. In 1835 the Treaty Party, a small faction of the Cherokee Nation led by Major Ridge, his son John, and Elias Boudinot, signed the Treaty of New Echota which sold the lands of the Cherokee Nation to the United States Government — opening the door for removal. The Treaty violated Cherokee law but it was all the U.S. Government needed to remove the Cherokee.

In 1838 the removal of the Cherokee began. General Winfield Scott, along with several thousand men, moved the Cherokee’s out of their homes and into stockades in Tennessee. However, the roundup of the Cherokee from their homes was just part of the story. From the stockades the Cherokee were forced, in several groups, from Tennessee and points east to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma).

The trip was harrowing. Many people died along the way from hunger, exposure, disease, and exhaustion. The trail was particularly hard on children and the elderly who died in the greatest numbers. Even before starting their trip on the Trail of Tears the Cherokee had to first survive the poor sanitation and close quarters of the stockade interment camps.

Though there are few records of exactly who started and finished the Trail of Tears it is estimated that some 16,000 Cherokees started the journey and about 4,000 were lost along the way. By March 1839 the Trail of Tears had concluded and the Cherokee found themselves in Indian Territory with their government, culture, and people in shambles.

But the strong spirit of the Cherokee would not be quashed. During the fall of 1839 the new Cherokee Nation re-elected John Ross as Principle Chief and ratified a Constitution of the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation has continued to thrive.

In 1987 the path of the Trail of Tears became a national monument and is a symbol of the wrongs suffered by Indians at the hands of the U.S. government.